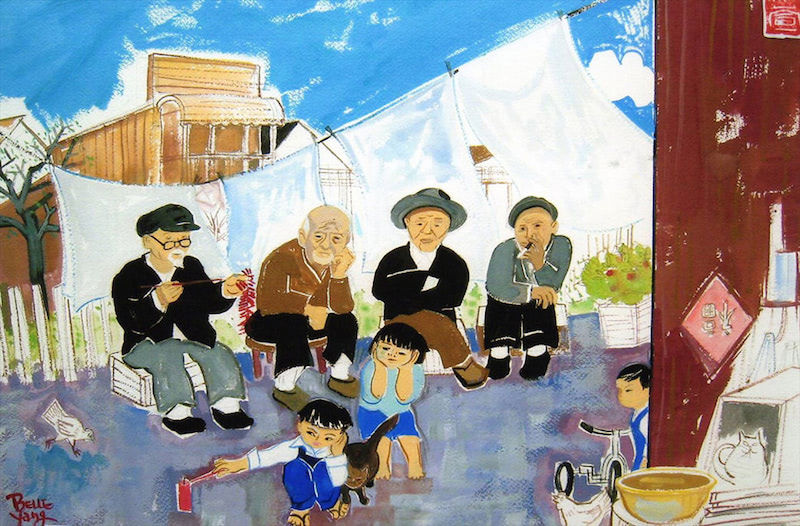

Belle Yang – Artist Statement

“Chinatown Uncles”

Uncles: Moon Lai Bok, Lee Lam Bok, Ah Fook, Yee Hen Bok

Children: George Ow, Jr., Georgina Wong, David Lee Ow

I’ve long wished to paint George’s chinatown uncles because I have also had the privilege of knowing surrogate uncles (who fled the Mainland to settle in Taiwan); they remained lifetime bachelors.

When an artist paints a portrait, she takes the subject deep into her soul. I had only old photographs for models, but I’ve made these men part of me. I’ve stared into their eyes and they too have become kin, my Chinatown uncles. I think this painting is one of my finest and among my favorites.

I had intended to work the sky with different shades of blue and patterns. But I loved the spontaneity of the “scumbled” effect of a single hue, I decided to leave it alone. The hardest aspect of painting (and writing) is knowing when to leave it alone.

–Belle Yang

There were once a lot of the old men like Grandpa Lee in Santa Cruz’s Chinatown. By 1947, however, the few left are dying off, one by one. Chin Lai, Ah Fook, Yee Hen and Lee Lam are quiet, competent old men. They know how to get free fish heads, how to cook dandelion and mustard greens they pick in empty lots, where to get mussels and clams at low tide, how to make tofu. They darn their own clothes and keep themselves company. They enjoy precious strands of tobacco gleaned from cigarette butts found on the sidewalk. They gather the tobacco in Prince Albert cans and roll their own.

Mostly, these old men spend their days sitting in the cool shadowy quiet of the old tong hall, which is decorated with pictures of Sun Yat Sen, Abraham Lincoln, George Washington and Chiang Kai Shek. The Nationalist Chinese flag and the stars and stripes are tacked inside, side by side on one wall. Once, this hall was filled with hopeful, energetic young Chinese men wanting to make their fame and fortune on “Gold Mountain,” which is what the Chinese called the United Sates. But laws and secret covenants devised by the white majority made sure the Chinese could not gain social or economic equality with the city fathers . . . .

When the work was done, these men were no longer wanted and were prodded—many times brutally—to leave. So they went from the sardine docks of Monterey to the lettuce fields of Salinas, from the cantaloupe harvests of Yuma to the apple orchards of Washington, from the asparagus crops of Stockton to the strawberry patches of Watsonville, from the fish canneries of Alaska to the avocado groves of San Diego.

Now these old men are at the end of their line. Not having families or children of their own, the old men are gentle and playful with the few Chinese children in Chinatown . . . . There was little hope of a Chinese male in America starting a Chinese family. And if Chinese women weren’t available, antimiscegenation laws made it illegal for Chinese men to “mix” with white women. The men knew that if they broke those laws, they could easily be lynched.

So, the old men are bachelors and my unofficial uncles. They have not seen Chinese children for so long that I am a wonder to them. They give me sweets and firecrackers. They see in my youthful hope and my father’s adult strength the dreams, the aspirations of their young manhoods. I can see the strength that once coursed through their bodies, but they are now slow and old—like the spent salmon that littered the San Lorenzo River after spawning-–shells of what they once were, ready to pass on . . . .

The year I was born, the anti-Chinese Laws are beginning to crumble. After all, China is America’s ally in the war against fascism, and it is bad public relations to have overtly racist laws against the friend fighting beside you. Dad would eventually become a citizen, vote, own land, have rights in court—in other words, “become legal.” My siblings and I will be able to go to college and work shoulder to shoulder with whites in any occupation we choose, a situation that was unimaginable to my grandparents and only a hopeful dream to my mother and father. I definitely was born under a lucky star.

–George Ow, Jr. in “Chinatown Dreams,” published by the Capitola Book Co., 2002